"Ringraziamento": Thanksgiving in Rome

Breaking bread, bending rules, and finding cosmic balance in gratitude far from home

For a notoriously anarchic population, where there’s a tangent to every law, and red traffic lights are a mere suggestion, order reigns at the table.

I’m not talking about the cappuccino conundrum—the notion that you can’t order one after noon, or (gasp!) after dinner. That’s a lie that refuses to die.

There are far stricter rules about coffee, and I’ve broken most of them to the dismay of baristas up and down the peninsula. With few exceptions, ice cubes in espresso elicit bewilderment if not beratement.

The traditional Thanksgiving feast is an abomination to the Roman palate.

Here, each course of the meal from appetizer to dessert (antipasti, primi, secondi, dolci, etc.) comes served on its own plate.

This has nothing to do with fine dining versus casual dining. I’ve had paper plates yanked away, and new ones thrust at me in the name of not mixing flavors. Non si mischiano i sapori.

I’ve been scolded for talking too much instead of eating (chiacchieri troppo e non mangi), warned that that the pasta will get all stuck together (la pasta si incolla), and that everything will get cold (poi si fredda).

I’m used to piling everything on one plate.

“I’m American, that’s how we do it!” I’ll gladly sacrifice the perfect temperature of a lasagna slice for the sake of storytelling. They shake their heads with a hybrid expression of mournfulness and pity when I plead, “It’s still delicious…”

Their House. Their Rules.

True belonging means to be a part of something, geographically, linguistically, but most of all, culturally. Living abroad means embracing local customs, however arbitrary or absurd they seem at first.

I’ve always felt grateful to be invited and included in meals like these.

My protestations have since evolved into more of a well-worn comedy custom of our own.

Roman friends warn servers that I’m American, I’m slow, and to let the plates pile up next to me. I’ll consolidate on my own time, and save them the horror of scraping the last of my carbonara onto a plate of meatballs.

Eventually their rules rubbed off on me.

I’ll never forget my first impulse to call guests in from the terrace for a plate of steaming spaghetti instead telling them to take their time and finish their cigarettes. It would be be pity for it to get cold and stick together…

I was also proud of my execution. Al dente and salted to perfection.

Legends of the Feast

When I introduced Thanksgiving to my Roman friends, they were enthusiastic (if skeptical) to taste “authentic American” cooking, and eager to hear the origin story of a holiday they’ve seen on film and TV.

Romans are no strangers to holidays inspired by historical events, mythological tales, and the blur of the two that has always drawn me to this part of the world.

We’ve since learned that the tender of tale of a shared meal between pilgrims and Native American Indians who helped them survive their first winter is at best a page torn from a diary entry. It’s hardly representative of America’s ultimately brutal land grab.

A Celebration of Gratitude

I always start with a short history lesson, which also explains the traditional dishes. I reiterate that truth or fiction, the universal takeaway from American Thanksgiving will always be gratitude.

Thanksgiving is inclusive, non-religious, and regionally adaptable.

In a nation of immigrants, you’ll just as soon find a deep-fried turkey, cornbread stuffing, and collard greens as you will sweet potatoes with a marshmallow crust and and gravy from a box (no judgement… but not on my watch)!

We all agree there’s no reason not to expand the celebration of gratitude overseas. So, why not on Rome? The recipes are bound to benefit from their sensational produce.

Gratitude (Gratitudine) is a Roman Virtue

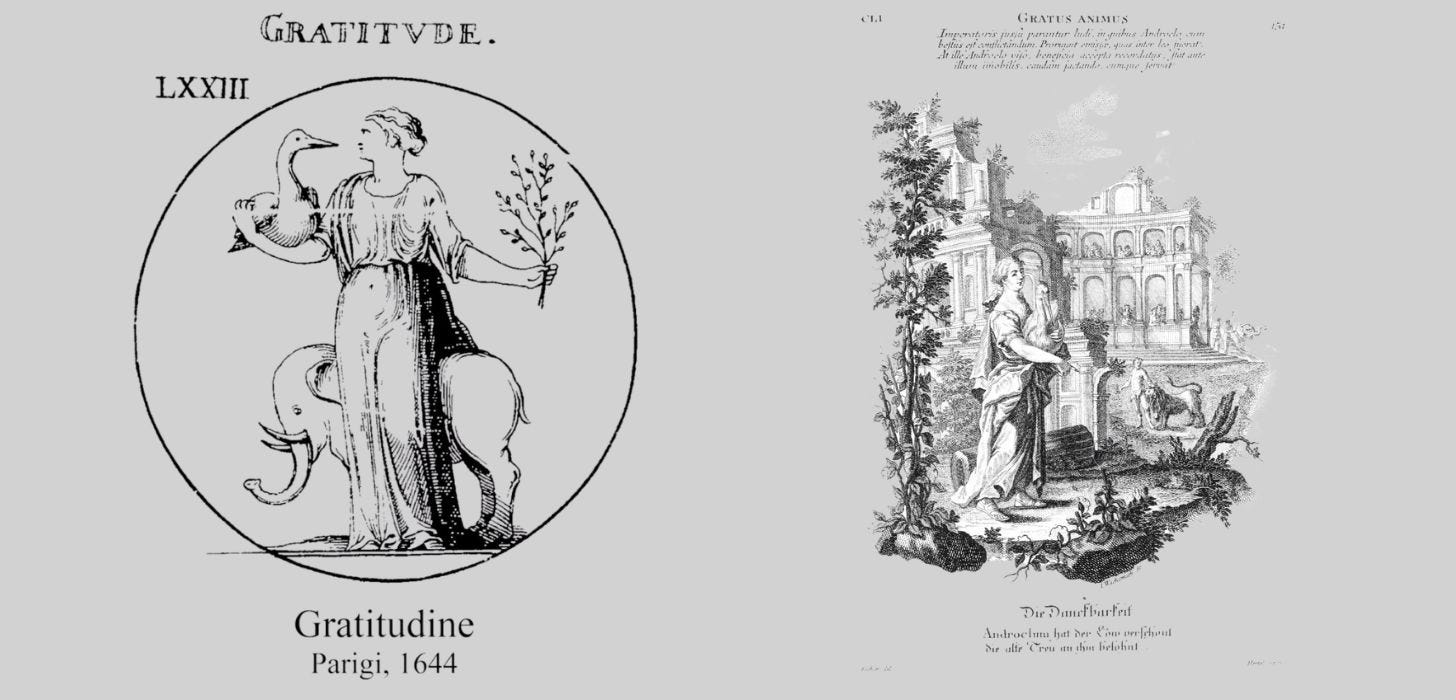

The word gratitude actually comes from the Latin Gratitudo (derived from gràtus), the sentiment or expression of thankfulness; the memory of a favor received and a readiness to show gratitude for it.

Ancient Romans glorified gratitude as a noble character virtue. Roman culture was built around favors (beneficentia), obligations, and reciprocity (officium), a dutiful response).

Gratitude was not only expected in noble society, it carried divine significance as a sacred practice.

In Ancient Rome, the virtue of gratitude appears on monuments as a woman holding a bouquet of fava bean flowers, often with a stork at her side—the flowers a symbol of ritual and memory, the stork of loyalty to family and lineage.

Renaissance imagery added an elephant to the figure of gratitude. The humanist symbol relayed loyalty, memory, and reciprocated kindness.

The universal law of cosmic balance

Karma appears in early Vedic texts and later throughout swathes of Eastern religions and philosophies. Ancient Egyptian artwork depicts scenes from the afterlife wherein the hearts of the dead are weighed against the feather of Ma’at, the goddess of cosmic balance.

Every Roman Thanksgiving has taught me something new about this city, deepened my attachments to local custom, and the relationships that helped me find balance asa foreigner in a whole new world.

A Tapestry of Tradition

I learned the hard way that turkeys must be reserved a week in advance from the butcher. For my first official Thanksgiving in 2006 we stuffed a chicken instead.

A year later, I ordered a bird too large for my oven.

I later learned from my butcher Eduardo at Carnidea, that it was probably a male. They’re bigger, and the meat is tougher due to testosterone.

Not only was it too large for my oven, but it still had some feathers attached, which I was instructed to burn off with a lighter. The feet required a serrated knife and gritted teeth.

Thankfully the restaurant downstairs offered to bake the bird for me. In Roman style, I acknowledged his favor (beneficentia) with (officium), a dutiful response—a glass of prosecco and a heaping plate of leftover pie.

This year, I’m expecting an organic Tuscan lady. Cluckerina de’ Medici, I’m grateful for you too.

My friend Eric J Lyman has a harrowing yet delightful turkey tale from his first Thanksgiving in Rome.

Variations on a Theme

During the early 2000s, I improvised a lot. I colored white potatoes with carrots and beets when yams were impossible to find.

I used a combination of scamorza and piquant, aged pecorino in place of the sharp cheddar cheese.

One year, I even added orange food coloring. For some reason that felt wrong in the potatoes, yet requisite for the macaroni and cheese. Blame it on the blue box we all grew up with and its thousands of unpronounceable ingredients.

Teardrops in my Apple Pie

I learned that while Romans can be outspoken and even crass in public, when forced to makes speeches around the table, they shrink into their seats.

Only after the last rounds of espresso and amaro (one of the many regional alternations I’ve wrapped into my menu), do they loosen up, get loud, and even get emotional.

I’m often the teariest of the bunch.

Overwhelmed by the spirit of the holiday, and grateful for a city that has not only embraced me, but shown an openness to embrace aspects of my American culture that I refuse to leave behind.

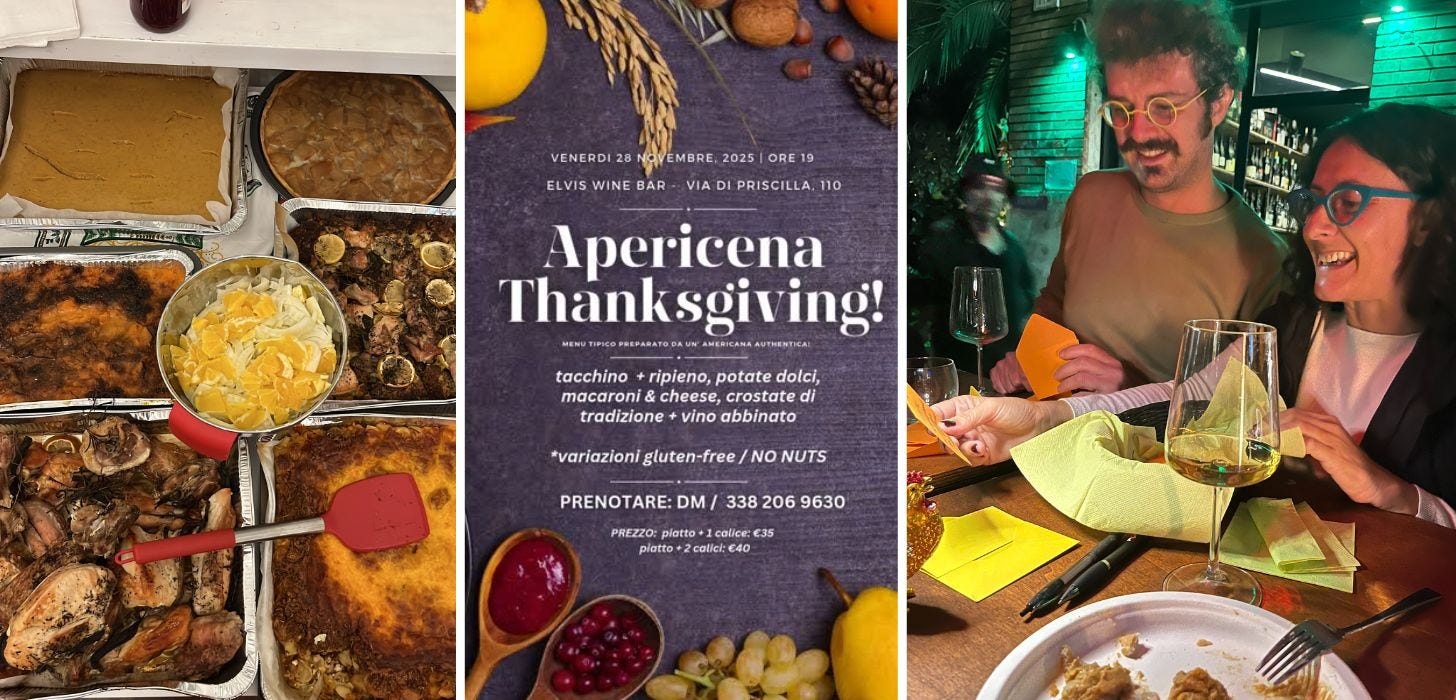

This year, for the second time in a row, I've been entrusted to cook for the customers at my local wine bar, Elvis. In Rome? JOIN US!

Last year was a success.

Food was piled high on plates, and no one complained, even when it got cold.

When it came time to express our gratitude, we solved the shyness problem by having guests write their sentiments on paper.

At the end of the night, we read them aloud, and then set our thanksgiving prayers ablaze. An offering of gratitude to the sky and a beautiful display of cosmic balance and belonging.

This year we’ll do it again, and I’m so thankful.