Rising to the Occasion

The explosive and enduring allure of Etna wines

In September, I waxed wistful about the end of summer—specifically, the weightlessness of being near water, and the burden of the retreating from the sea and back to reality.

I wish I could drift into fall sweaters with the grace of a wafting red leaf.

This month, with harvest well underway, we enter a period of anticipation and uncertainty. There’s a nervy excitement to gathering and refining the fruits of our labor before the sun sets and the year ends. Both too soon.

It helps to embrace the energy of the wine harvest and look forward to soul-warming red wines we’ve been putting-off all year. Etna Rosso is a great place to start.

Read on to learn more.

Last year I profiled three wineries on their harvest rituals.

The Energy of Etna

Nowhere on earth embodies verve and harmony in the face of uncertainty like Mount Etna.

Last month, I joined writers, educators, and wine communicators from all over the world for five days of full immersion into one of Italy’s most fascinating wine regions.

Europe’s largest and most active volcano, Mount Etna stretches 3,400 meters above sea level at its highest peak. Etna wineries grow and produce as high as 1000 meters, and some growers have successfully surpassed that. Stef Kim, of Azienda Agricola Sciara is pushing 1,500 at his Cielo (sky) Cru.

There’s a propulsive energy to this place, an undeniable impulse to rise before dawn. A reminder to always look up. I felt it. We all did.

On just four hours of sleep, after-dinner amaro still hot in my veins, I awoke each morning before the alarm, eager to breathe the first fresh air.

Gods and Monsters

On Etna, I leapt out of bed, incredulous and exhilarated. I’m certainly not the first to wonder at this phenomenon.

Evidence of Greek civilization marks the terrain, and Etna teems with magic and mythology.

Mount Etna derives from Aítnē (Αἴτνη), from the Ancient Greek αἴθω (aíthō) “to burn.” According to legend, Athena defeated the giant, Enceladus, and imprisoned the creature below the mountain.

Enceladus and the other giants were born of Gaia, Mother Earth, who raged against the Olympians for usurping power from the Titans, her original offspring with the sky (Uranus).

The Greeks attributed the mountain’s rumbling and eruptions to Enceladus’ fiery breath and quaking fury.

Athena’s actions transformed Etna into a living being.

The meeting of the geological and the divine symbolized the eternal struggle between cosmic order (Olympus) and the chaotic forces of the earth.

Life on Etna is a reminder to nurture the land and respect the whims of nature.

Like Athena, growers on Etna have harnessed the fulminating qualities of their terrain to create living, breathing wines.

Little Trees, Deep Roots

We arrived just before harvest. Sun-swollen grapes still clung to the vines in what resembled little orchards.

Alberello is Italian for 'little tree.’

The bush-training technique has been employed for millennia on the arid volcanic soils of the southern Mediterranean. Trained low the ground, plant steel themselves against a battery of wind and rain. Plants casts their own shade. Their roots run deep in search of underground springs.

Irrigation is prohibited except in extreme cases. Coltivazione a secco, literally, ‘dry cultivation’ teaches the plants to quench their own thirst, enabling them to survive long periods of drought.

Indigenous varieties thrive at soaring altitudes and severe conditions.

Nerello Mascalese

Named for Mascali, an ancient settlement at at the eastern base of the volcano, bordering the sea, Nerello Mascalesi has always dared growers to go higher.

With its sculptural acidity, Nerello shares a similar austerity, and semi-transparent ruby red color with Nebbiolo and Pinot Noir. It produces aromas of piquant red fruit, savory vegetal notes, black pepper and volcanic ash (to name a few).

As it ages, Nerello Mascalese silkens out and exudes a panorama of elegant notes of tobacco and leather, jammy fruit, and dried flowers, and sweet smoke.

Nerello Cappuccio

Darker-skinned and rounder in every way, especially on the palate. Nerello Cappuccio rarely shines as a star player, though when it does, it’s extraordinary. Benanti, and I Custodi both produce one under a the Terre Siciliane IGT classification.

Nerello Cappuccio brings rich color, silky texture, and brighter fruit to Nerello Mascalese’s muscular structure, and intrinsic smoke and spice.

Carricante

The reigning white variety for Etna Bianco. Carricante produces astonishingly plentiful fruit, its name derives from the Italian word, carica- a nuanced Italian adjective encompassing full, charged, energized, loaded-up, and energized.

Carricante shimmers in the glass like sun striking the sea, and acts as an olfactory mirror for its surroundings.

Aromas range from ripe stone fruit, honeym and hay, to sweet greens like wild fennel and tarragon, and the citrus-tinged, nepitella, wild mint that grows everywhere.

At the front, wet stone and smashed gravel. On the finish, mouthwatering sapidity.

The relentless and resilient qualities of the grapes come through in Etna wines.

Mountains ground us in space. Their majesty is humbling, their existence a reminder that there is history below the soil, a whole world rumbling deep below.

Like the vigorous vitis vinifera vines we trace our own roots deep. We grasp at tradition to ground ourselves on a shifting earth.

With over 100 microclimates, and millennia of volcanic activity streaking the soil, there are innumerable variations to the red and white wines produced on Etna’s slopes.

Wine growers and producers embrace the wild and robust qualities of both red and white varieties and tame them through time.

Aging in steel and cement tanks, wood barrels, amphora, and even in the bottles gives wines a chance to relax and release their compelling aromas.

A common thread is the endless savory, sapid finish, reminiscent of the volcanic stone and the sea below.

To live on Etna is to remember where you came from.

We engrave the names of people and places and stories on our memories. Sharing all of this with you is an exercise in revitalization.

A new friend of mine, Kevin Tyler, wrote of our experience, “I hope to breathe a second life into the handful of moments I collected during this five-day tour, and treat the stories I’ve been handed with the same gentle care with which they were given.”

Read his piece here.

The ancient epics served as a thread of life.

Reliving and recounting days on Etna and drinking the wines that tell their own stories in scents and flavors is akin to living innumerable lives.

To understand Etna is to see trees sprout from stone.

Imagine the ground beneath your feet, the place that defines you—your looks, your language, the adjectives that describe you—at some point in prehistory blasted out of the sea floor in broils of lava that cooled and settled on itself for millennia until an island was born.

From the core of the earth’s fiery heart sprang life. How long it must have taken for the first signs of it to show above water, for the first grasses to coat the coastline, and climb toward the mouth of their mother, who would one day rain ash and fire upon them, killing her own creations so newer, stronger ones could grow in their place.

Etna Wine is a tale of constant rebirth.

The Greeks brought viticulture to Mount Etna as early as 8 BC. The Romans adopted their practices, and expanded production. Roman historian, Pliny the Elder documents the precious Vinum Aetnaeum.

Following the fall of Rome, monasteries kept viticulture alive. We can thank communion wine and thirsty clergy for that.

During the rise of Renaissance trade, Etna wines reached beyond Italian shores and reclaimed their reputation as high quality wines. Under Spanish rule and the Bourbon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (pre-Italian unification) the trend continued.

By the late 19th-century, a plague of phylloxera (aphids) devastated vineyards across Europe, reaching Etna around the 1880s. A mass exodus ensued, leaving many of Etna’s vineyards abandoned.

Rise of Modern Etna

The late-20th century saw a return to the land and surging faith in Etna to produce stellar wines.

The resurrection of Etna wine credits a number of visionary producers with fueling the flames.

Growers and oenologists including Giuseppe Benanti, Salvo Foti of I Vigneri, the Nicolosi-Asmundo family at Barone Villagrande, Alice Bonaccorsi of Valcerasa, and Marco de Grazia of Tenuta Terre Nere, along with similar minded producers breathed new life into viticulture on the volcano.

Many of the wineries we visited were in their second or third generation.

Ciro Biondi, another pioneer of the late 20th century, has reclaimed the reins of his Great-grandfather’s 1800s-era estate on land his family has been cultivating for four centuries.

New wineries work constantly to recover old vines and preserve indigenous grape varieties. The majority farm organically and employ regenerative practices to protect their soil.

The winemakers on Etna talk about the volcano as feeding them, as caring for them.

I ask Alice Bonaccorsi what’s it’s like when Etna erupts more violently than usual, spewing black clouds that rain ashy debris.

“Etna is like part of the family,“ she says. “We know it’s good. It helps us, it’s not an enemy.”

They are not afraid of her, although evidence of her past destruction is everywhere.

Sciare, the hardened rivulets of lava sit in plain sight still. They present as piles of stones in many places now, black-brown pumice rock now. They slice through the wineries like irrigation channels. In some places, whole forests have sprung up on top of them.

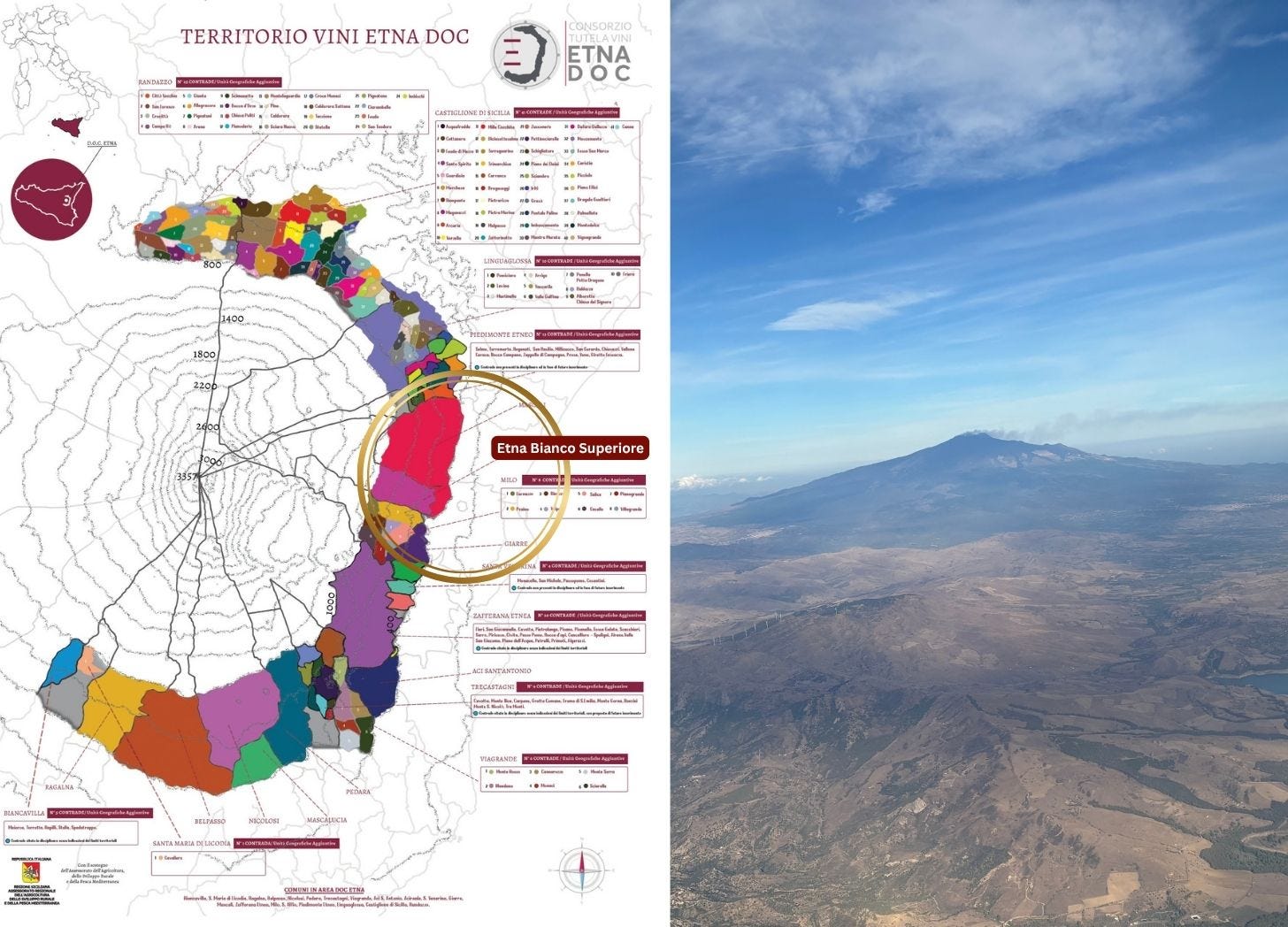

Crus and Contrade of Etna

Contrada or plural, contrade, are historically delineated wine-growing areas on Etna. The 133 contrade were carved out over the years based on altitude, soil analysis, and the qualities of the wines typically produced in the area.

For comparison, think of Burgundy Crus like Chablis, Côte de Nuit, and Côte de Beaune.

Click and zoom in for a detailed Etna map.

During Etna’s renaissance last century, producers began labeling their wines by contrada to indicate their location on the volcano, as opposed to simply writing Etna Doc Rosso (red) or Bianco (white).

Etna’s terrain and microclimates are so vast, that many wineries bottle from single vineyards, which they call crus or tenute (pronounced: teh-noot-ay).

Growers study maps of past eruptions to understand their soil.

On the eastern slopes of Milo, the soil is black following constant ash rains and millennia of lava streams.

Toward the base of the hill, closer to the coastline, there is more sand and clay, the original material of the volcano.

At Maugeri, sisters, Carla, Michela, and Paola, along with their father Renato, carry on a family legacy that was abandoned last century. At around 700 meters up, part of their property faces the Ionian sea, and the rest faces the mountain.

They’ve delineated crus on the property and they plant accordingly, taking into consideration sun and shade, exposure to light and the constant beating breeze.

They read the earth and interpret the wind. In the glass Etna is reborn again.

Next month on Etna

Ciro Biondi gets a visit from a magical moon goddess, Etna founding mother, and renegade in her own right, Alice Bonaccorsi of ValCerasa, and why Etna Rosso reds smell like incense.

For paid subscribers: tales and tasting notes from MAUGERI + a simple, stunning herbed crouton recipe