Baked to the Gods!

The Ancient Art of Serving Spirituality in Cookie Form

For some of you it’s Christmastime, for others, holiday season.

It’s hell on earth if you’re working retail or flying in and out of a major US city, and heaven for homemakers and bakers.

No matter where you stand on the spectrum of holiday cheer, if you’re a resident of the western world right now, it’s cookie time.

Cookie Time

As Troupe Beverly Hills taught us, cookie time is a vibe. Sure, they had sales goals to hit. And that movie is about Girl Scouts, not Christmas, but as a metaphor, who hasn’t been there?

Between the shopping and the selling, ‘tis the season for transactions.

Home-made cookies are a welcome departure from buzzing Christmas consumerism. The humble gesture actually has roots older than the holiday itself.

For the Love of G-D, Preheat the Oven

Humans have been baking as a gesture of religious reverence since antiquity. Egyptians are some of the earliest bakers on record and were known for seasoning their flatbread with honey.

Sumerians in Mesopotamia integrated dates, figs, and nuts into breads and cakes. Assyrians in Babylonia were using sesame seeds at least 4,000 years ago.

Many of these recipes have distinct through lines to local delicacies you can still find throughout the region thousands of years later.

Andalusian pan de higo is a direct descent. Ma’amoul, or date-stuffed cookies are a staple in the Levant and very likely a precursor to our own Fig Newtons.

Halwā is a romanized version of the Arabic root: ح ل و, ḥ-l-w and means "sweet".

Today, halva is popularly known as ground and pressed sesame seeds and is ubiquitous throughout the cuisine of the southern Mediterranean and North Africa. Early uses of the word, however, refer to a date paste that originated in Arabia or Ancient Persia.

Honey cakes or syrup or honey-soaked confections like basbousa and nut-laced baklava and kunafa, knafeh, and kunefe are pervasive throughout the southern Med and Middle East.

Italian cantucci (almond biscotti) as well as pangiallo and panforte, a mash of dried and candied fruit, citrus zest, nuts, chocolate, and honey clearly trace their origins to ancient times. Hello fruitcake!

Say Cheese

Greeks and the Romans added cheese to the mix. Sheep cheese especially.

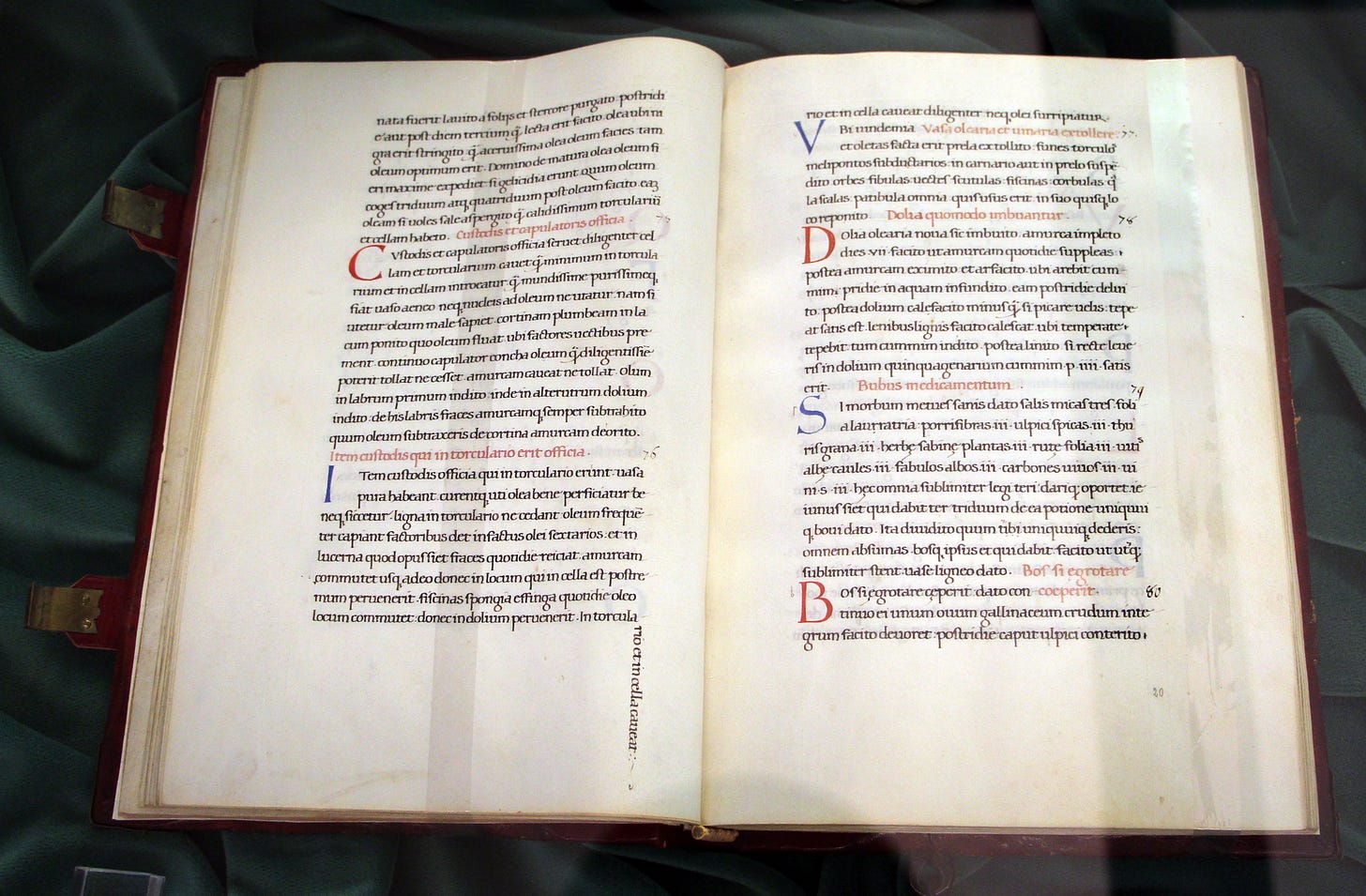

Some of the earliest recipes on record appear in Cato the Elder’s De Agri Cultura (circa 160 BC), an accounting of Roman agricultural practices and traditions, including cuisine.

Libum was was an unleavened, small cake made with three ingredients available in most households: 2 parts fresh ricotta-like cheese (cow, sheep, or goat), 1 part flour, and honey (for drizzling). Cato’s recipe included an egg, likely as a binding agent.

The dough was shaped into small loaves or buns, pressed and cooked atop bay leaves in a hot stone oven.

Libum was initially prepared during festivals honoring domestic gods like Lares and Vesta as an offering of gratitude, a precursor for our own habit of leaving something for Santa Claus? Maybe.

Want to give Libum a go? This video is entertaining and informative!

The simplicity of the recipe lend itself to elaboration and variation, and eventually libum infused day-to-day baking as well.

A modern-day savory loaf can be found throughout Rome and the Lazio region around Easter, called pizza pasquale.

Placenta What?

Another Ancient Roman confection from Cato’s recipe collection is perfect for Jesus’ birthday.

Placenta, a Romanization of the ancient Greek plakous (flat), was derived from a Greek recipe made from layers of dough stuffed with cheese and honey and seasoned with herbs.

Recipes throughout Greece incorporate nuts as well, and the dish is generally considered to be the precursor for baklava, and other desserts like tiropita, a flaky cheese pie, as well as Bulgarian banitsa, a spiral-shaped cheese stuffed pie.

Plăcintă is a Romanian and Moldovan variation on the theme.

The anatomical term placenta does seem to get its name due to its resemblance to the ancient cake. Google at your own risk. I’ll save you the imagery side-by-side.

On the Greek island of Lesbos, the dish still goes by the name platsenta (πλατσέντα). Make of that what you will.

Thank You, Jesus

In the same way we owe monasteries for preserving the art of winemaking (they needed it for communion, and come on….spiritual existence), we can thank Christianity at large for swooping in and adopting the habits of their would-be converts.

As Christianity spread, it absorbed existing ancient and indigenous practices of preparing foods as holy offerings.

Bakers in Medieval Europe embraced the traditions and amplified them during the most significant holidays, namely Christmas and Easter.

The advent of Christmas markets in Germany and throughout northern Europe, further cemented the ritual of baking and sharing sweet treats with friends and family as token of goodwill and generosity.

Fast forward to today.

They might not be the best blondies you’ve ever tased, but when it comes to baking, the thought truly counts.

I used to think baking was a smart and delicious way to save cash on gift shopping, but time is money. This year’s blitz yielded 200 orange-scented butter cookie hearts and a kilo of almondy glaze, but I’m still finding flour and powdered sugar in crevasses I didn’t know existed.

Try this recipe + two more, here.

Global Goodies

Christians aren’t the only ones stockpiling cookie tins and dusting off their rolling pins come holiday season. The tradition of sharing sweets to commemorate religious festivals spans the globe.

The Hindu holiday Diwali, also known as the “Festival of Light,” is celebrated by nearly a billion people around the world. Regional and religious interpretations and traditions abound. In addition to garlands of colorful lights and joyful décor, sweet and scrumptious snacks are a Diwali signature.

Electric-orange, saffron-scented Jalebi, crispy spirals of fermented dough drizzled in syrup, and gulab jamun—deep-fried balls made of khoya (thickened milk) and soaked in a rose and cardamom-flavored sugar syrup—are among an exhaustive list of Diwali delicacies.

Rightfully so, Ramadan wraps up with Eid al-Fitr, a proper feast wherein families and friends exchange food and sweets as a display of gratitude and generosity. These include: dates, sweet pastries like baklava and sheer khurma (made from milk, dates, raisins, and roasted vermicelli), among other regional delicacies.

During an Autumn Festival observed throughout China and parts of Vietnam, families and friends exchange mooncakes, a symbol of unity and the full moon.

During Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, apples and honey cake are all the rage. The early-spring festival of Purim celebrates survival with symbolic sweets inspired by stories from the Book of Esther, including triangular poppy seed and fruit-filled pastries called hamantaschen or oznei haman, named for Haman’s, the villain of the story.

Twice-Baked Biscotti

The modern Italian word for cookie or biscuit is a clear derivation of the Latin bis coctus, meaning “twice baked.”

Biscotti, in their original iteration probably looked a lot like the biscotti we know today, packed with nuts and dried fruit. Like hardtack bread, they were dry and baked to a rock-hard crunch, which made them easier to store for long periods, and for soldiers to take on the road during battle.

Cooking the Books and Baking the Biscuit

Italian idiomatic expressions and slang frequently have with food at their heart. Potatoes, strawberries, figs, and gnocchi have NSFW anatomical alter egos.

These expressions are safe for all ages:

Nella botte piccolo, c’è il vino buono. Good wine comes in small barrels, ie, good things come in small packages.

Il pesce puzza sempre dalla testa. The fish stinks from the head. Whoever’s in charge is the reason things are going wrong.

Fare il Biscotto

The expression Fare il Biscotto (bake the biscuit), draws from the process of baking cookies, which requires meticulous planning and execution. Generally it refers to careful planning and a guaranteed outcome.

Add to that, the etymological root “bi” for both, and you have two sides colluding or collaborating to insure a deliberate outcome. The expression gained traction in the 20th century as a football/soccer slang reference.

When two teams conspire to produce a mutually beneficial result, for example, a draw that would allow both teams to qualify for the next round of a tournament, while eliminating a rival team.

Infamous, albeit unproven allegations of “biscuit-baking” occurred during the 2004 EUEFA Euro Championship. Italy’s elimination was rumored to have resulted from a 2-2 tie between Sweden and Denmark that secured their advancement.

Rome’s Contemporary Cookies

Modern Italian refers to all cookies as biscotti.

Throughout the country, regional specialties reign. Naturally, some cultural and geographical crossover exist when it comes to more generic recipes like frollini or pasta frolla (shortbread), baci di dama hazelnut and chocolate-filled tiny sandwich cookies (lit. “the lady’s kiss”), lingue di gatto (“cat’s tongues” for their long, ovular flat form), and occhi du bue (“ox eyes”), perfectly round butter-cookie disks with a inner circle filling made of chocolate or jam.

Roman Specialties Include:

brutti ma buoni: The name translates as “ugly but tasty.” The crunchy and crumbly confections originated in northern Italy but have become a Roman staple. They’re made of meringue and stuffed with chopped hazelnuts and or almonds and spices.

ciavattone romano: Like ciabatta, the name is a take on its slipper-like shape. Virtually unknown outside of Rome and the surrounding area, this puff pastry is coated in caramelized sugar and stuffed with pastry cream.

ricciarelli: Light and chewy spirals (riccio=curl) made from almond-flour and egg whites

ciambelline al vino: crunchy ‘ little rings’ made with flour, olive oil, and red or white wine and occasionally flavored with anise seeds. Ubiquitous after-dinner treats, they’re designed for dunking in wine at the end of the meal.

You find all of these and more at Rome’s beloved, family-run bakery, Biscottificio Innocenti, originally founded in 1940.

Read more about the story, and meet Stefania, the third-generation captain of the kitchen.

I’d love to hear more about your favorite cookie discoveries in Italy and beyond.

Have you ever tried to attempt them back home? Jump in the comments and share your stories!

Happy Holidays!